An artwork by Nathan Cohen and Reiko Kubota created for an exhibition in Kyoto, Japan in July 2017.

Authors: Nathan Cohen and Reiko Kubota

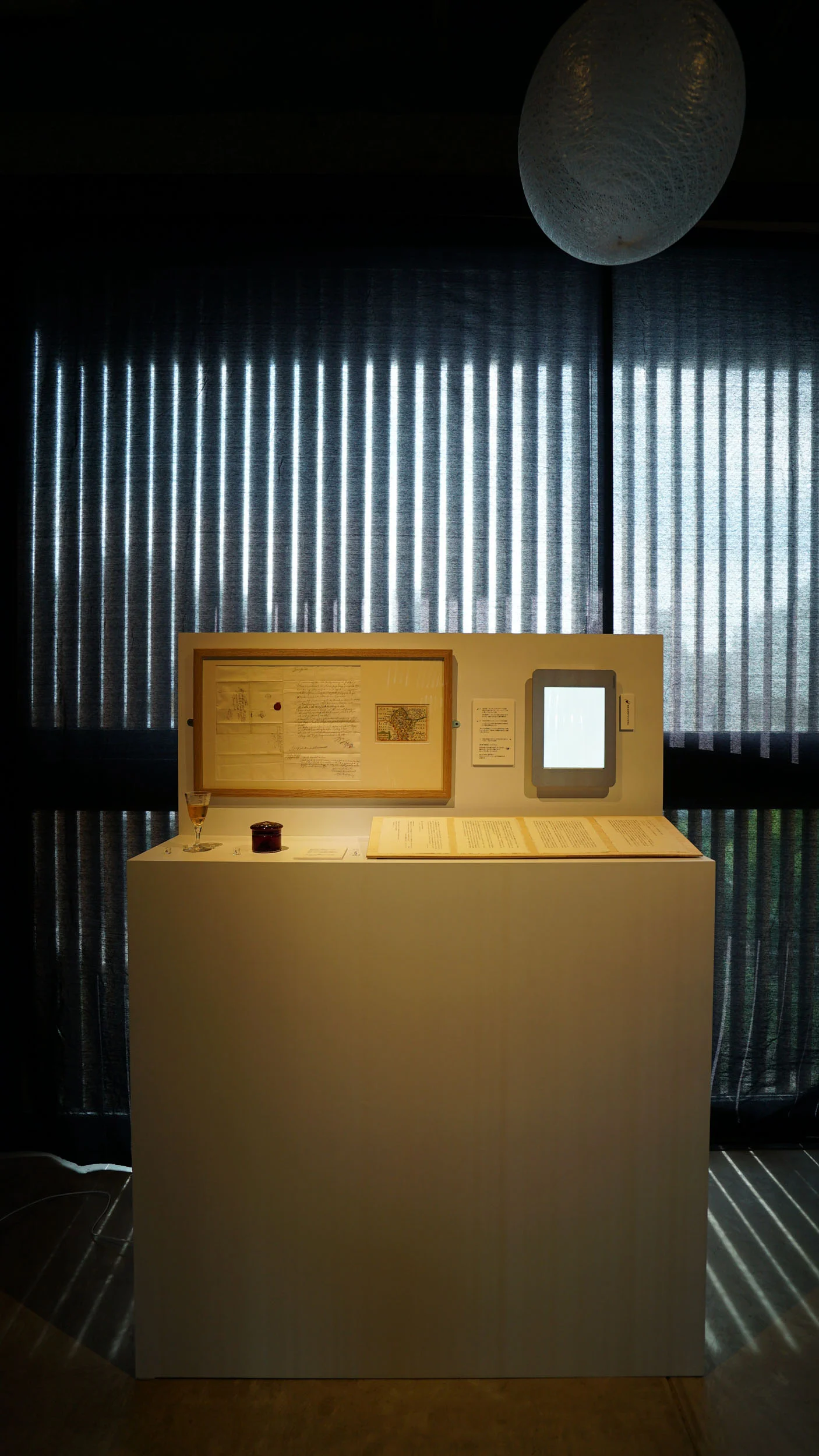

Image 1: Viola Odorata installation- Forum Kyoto Gallery

Petite Balade exhibition - evolution and context

Between 7 - 9 July 2017 an exhibition titled Petite Balade was publically displayed at the Forum Kyoto gallery in Kyoto, Japan. This was the first presentation by the group of international artists engaged in the olfactory art and science research project funded by KAKENHI (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research) in Japan. The exhibiting artists are: Yasuaki Matsumoto (Japan), Yoko Iwasaki and Takumi Tsukahara (Japan), Boris Raux (France), Ansiqi Li (China), Reiko Kubota and Nathan Cohen (UK).

The project was initiated by Dr. Yuriko Sugihara, Doshisha Womens’ University, with collaborating researchers from diverse specialist areas ranging from universal design to psychology and received a KAKENHI grant in the neo-gerontology category which approved funding over 3 years (2016/2017/2018).

The Forum Kyoto is centrally located near the historic Gion district of Kyoto and is a focal point for cultural and social activities in the neighbourhood, established by the artist Alexandre Maubert. It is a flexible and engaging space with several floors connected by a central open plan staircase offering different ways to engage with its architecture in the location of the artworks.

This text is an account of the artwork presented by us for this exhibition and the thinking behind its creation. This was the first time we have created an artwork collaboratively although we have exhibited our own work together in earlier exhibitions.

Process for creating artworks for the exhibition

When commencing a project that will ultimately lead to the creation of new artwork it can be challenging to determine how best to proceed. This is particularly the case when the parameters for the choices being made are in part determined by a desire to evolve a way of working that embraces the wider project aims and the inclusion of smell as a medium.

The participating artists had discussions over a period of months leading up to the exhibition to determine that there should be a focus on creating artworks that would explore the theme of natsukashisa, a Japanese term to describe the invoking of memories that may also impart a sense of well being. The artworks were each quite different and worked with a range of media including video projection (Yasuaki Matsumoto), installation with audio components (Yoko Iwasaki and Takumi Tsukahara; Boris Raux), film (Ansiqi Li), and interactive installation (Nathan Cohen and Reiko Kubota).

At the initial stage of planning the exhibition it was decided that there should be a single smell that all of the artists should include as part of their artwork, although this proved to be one of the most challenging issues to resolve. Our response to smell is personal and sourcing just one smell that all of the participants could agree to feeling natsukashisa required discussion and the sampling of different smells.

As part of this process it was decided that we should collectively agree on a context for natsukashisa which a particular smell might invoke and this resulted in choosing a type of place where this might be encountered and which all the participating artists would have some experience of. The final choice was for a wooded space that could be found by walking in hills or mountains, which may illustrate how subjective memories of olfactory experiences can be. It is also interesting that all of the participating artists live and work in cities yet selected for this project a smell that would invoke memories of more pastoral spaces.

As we had already determined that we would be using an additional smell, violet syrup, for our installation we actually displayed two smell samples which offered a broader olfactory experience while being in keeping with the theme and content for the exhibition.

The artwork - Viola Odorata

Image 2: Viola Odorata installation

To begin the process of making this artwork we had to consider various factors including what the contents should be and the logistics for installation.

We felt that the requirements of the project brief should be reflected in the choices we make and that there should be a sense of intimacy evoked by the artwork and how people would encounter it. This then led to considering objects we encounter in our lives that could invoke memories and that appear to have a history.

Image 3: Viola Odorata installation - letter (1673) and map of Staffordshire (1666)

Some months earlier we had acquired the first letter in what has subsequently become a collection of early postal history. We were intrigued by the content written in 1673 by a husband from the family estate in Staffordshire to his wife, the Lady Gerard, who was visiting London at the time. While the central part of the letter's text concerns matters relating to the family there is an interesting additional section written by their physician who is treating her son with violet syrup. Being derived from the flowers of the plant (Viola Odorata) this has a distinctive smell and offers an interesting connection between a natural herbal source of smell that is also curative for human health and the landscape.

With this as a starting point we wished to develop a narrative that was personal and could be related to by others. The letter itself offered a means by which we are able to relate to the thoughts and experiences of the letter writer and his family despite the span of time. Violet syrup is still available and used today and this allowed us to bring the experience into the present, with a sample presented in a period crystal glass with floral engraving, as part of the exhibition display.

Image 4: Viola Odorata installation - violet syrup smell sample

We also wished to make a connection with a specific place, in keeping with the theme for the show (the title Petite Balade is a French term for a stroll or short walk) and as the letter originated in Staffordshire we found a map of the county that was printed in London during the same period. These were framed together for the exhibition (see Image 3).

Maps evoke a sense of a place with details of landscape and geography noted. Old maps also imbue a sense of nostalgia, their form imparting an intimacy with a region that can resonate even if we are not familiar with the place depicted. This particular map is small and would have been included in an atlas of the British Isles. Interestingly, it was published in 1666 by Roger Rea*, the year of the Great Fire of London that devastated much of the city. Drury Lane, the location in London where Lady Gerard was residing when she received the letter was spared from the fire.

Image 5: Viola Odorata installation - woodland smell sample pot

To create a complimentary symmetry in the installation we therefore placed a wax sample of the woodland smell we had collectively chosen as being common to all of the exhibits in a small lidded red glass pot that was decorated with a gilt pattern. This gave the sense of a period piece in keeping with the time of the letter although this pot dates from the late 19th century.

This describes the objects and images that viewers could interact with as one part of our display. But we also wished to take the content and develop it within a contemporary context, and to this end we worked with two other contributors.

Image 6: Viola Odorata installation - Hiromi Ito letter

Hiromi Itō is a well known Japanese poet and novelist who we invited to interpret the original letter contents by writing her own version of what she imagined the letter Lady Gerard may have received from her husband might have been.

This required producing a transcript of the 1673 letter in modern English together with a translation into Japanese, and then engaging in a dialogue with Hiromi regarding the letter content, theme for the exhibition and context within which her letter would be presented. As part of this process Hiromi researched the social, cultural and historical background and how plants and landscape were cultivated in rural 17th century England. The resulting text presents her own interpretation of the source materials and was then printed by us onto handmade paper sheets of letter size for the exhibition display.

Image 7: Viola Odorata installation - interacting with Yu bi Yomu digital display

Above this viewers could interact with a digital display on an iPad that depicted the final page of Hiromi Itō's letter. This was provided by Dr. Junji Watanabe, who developed the interactive digital interface with Dr. Kazushi Maruya, and was displayed in the exhibition with permission from NTT Communication Science Laboratories , Japan. This is a unique haptic display format called Yu bi Yomu (which translates approximately in English as 'finger-reading') where text on the iPad screen is palely visible until touched by a finger, when it then becomes bold enough to read before fading after a few seconds. This requires the viewer to physically interact with the screen to read the text imparting a sense of writing the words as you follow them with your finger. The gradual fading suggests the moment passing with time.

Conclusion and future development

There are a number of ways in this artwork in which we have explored notions of memory, time and place in the context of smell, encouraging viewers to immerse themselves in a narrative that we hoped would resonate at a personal level and that might also evoke a sense of well being, in keeping with the project aims. As a first step we wished to learn more about how people would respond to the different elements and from observation we noted that many chose to spend some time reading, touching and smelling the exhibits as they navigated their way around the installation.

This interaction between different elements and the engagement encouraged through visual, haptic and olfactory experiences we feel offers the potential for developing interactive objects the content of which can be personalised with their own or their family's memory associations . This could address the overarching project brief, to design a form that induces natsukashii feelings that an individual with memory impairment can associate with, and to this end we will next be exploring how this may be achieved with an intimacy of scale.

We are grateful to the following for their contributions to the organization of the exhibition:

- Dr Yoko Iwasaki - Project Arts Director

- Prof Yasuaki Matsumoto - Professor Media Art, Kyoto Saga University of Arts

- Dr Yuriko Sugihara - Olfactory Art and Science Project Director, Doushisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts

- Hiromi Itō - Poet, Novelist

- Dr Kazushi Maruya and Dr Junji Watanabe - Creators of Yu bi Yomu

- Alexandre Maubert - Director, Forum Kyoto

- Hila Yamada - Assistant to Dr Yoko Iwasaki

- Akio Tsuji - Videographer and Photographer

- Ismael Franco Alvarez - Olfactory Art and Science Research website designer

- and the team of students from Kyoto Saga University of Arts who helped with the exhibition installation and invigilation.

We would also like to thank NTT Communication Science Laboratories , Japan, for permission to display Yu bi Yomu as part of our installation.

Photography and video credits:

- Images 1 - 3; Video clips 1, 2 - Akio Tsuji

- Images 4- 7 - Nathan Cohen

References:

- Yu bi Yomu display: http://www.kecl.ntt.co.jp/people/maruya.kazushi/Yubiyomu/

- Hiromi Itō, poet and novelist: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiromi_It%C5%8D

- *Map of STAFFORDSHIRE, published by Roger Rea, London 1666 in: "England Wales Scotland and Ireland Described and abridged with ye historie relation of things worthy memory from a farr larger volume done by John Speed"

- A 17th century copper engraved miniature map of Staffordshire by Peter Van Den Keere, from a pocket edition of Speed's atlas which survived the 1666 Great Fire of London that destroyed the heart of the capital city and badly damaged important landmarks including St Paul’s Cathedral and the Royal Exchange.

© 2017 Nathan Cohen, Reiko Kubota

All rights of reproduction reserved.